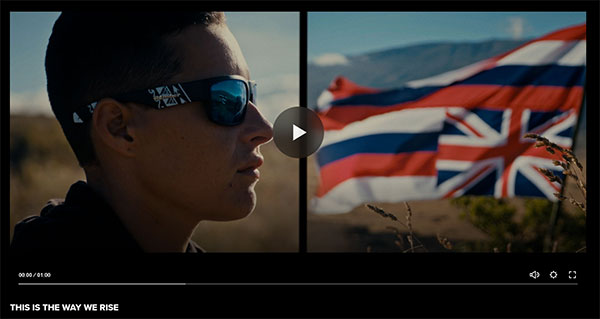

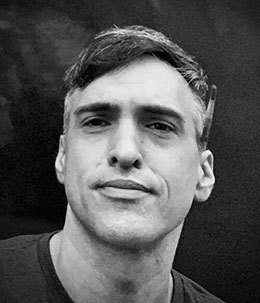

Native Hawaiian visionary Kēhau Noe is an artist and storyteller . Her media is computers, and her mission is to design programs that help people to interact with and learn from the environment.

. Her media is computers, and her mission is to design programs that help people to interact with and learn from the environment.

The challenge of building software or games that take advantage of what technology affords us, but still be accessible and useful to the general person is fun to me. Software can be capable of performing complex and seemingly impossible tasks, but if the average person does not like to look at it, or can’t understand how to interface it, then not many people will use it.

Her innovative storytelling immerses viewers in the Native Hawaiian world view. We are pleased to feature this trailblazer on our blog today.

For those who havenʻt met you yet, could you please tell us a little about yourself?

I’m Kari Kēhaulani Noe, I usually go by Kari or Kēhau. I was born and raised on Kauaʻi and moved to Oʻahu to go to the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa for my undergraduate degree to major in both Animation and Computer Science. I am now pursuing a PhD in Computer Science at UHM. I work as a research assistant at the Laboratory for Advanced Visualization and Applications (LAVA) where I also co-lead Create(x), a sister-lab managed by both LAVA and the Academy of Creative Media (ACM) at the University of West Oʻahu. I also work as an Indigenous Tech Specialist at the Office of Indigenous Knowledge and Innovation. I also have my own studio, Studio Ahilele, where I work on creative projects and collaborations on the side.

In my personal life I love nerdy things. I often will be drawing comics, trying out some kind of art form (I’m learning carving at the moment), and playing video games in my free time. I also love hula and have been studying ʻōlelo Hawai’i.

Where did you grow up? What high school did you grad from?

I grew up in Kalāheo, where most of my time was spent hanging out somewhere in the west or south side of the island as that is where most of my family lives. And of course Līhuʻe as that is the main town and where my high school is. I graduated from Kauaʻi High School.

Go Red Raiders! What are your goals for the Create(X) lab you co-lead and for your research?

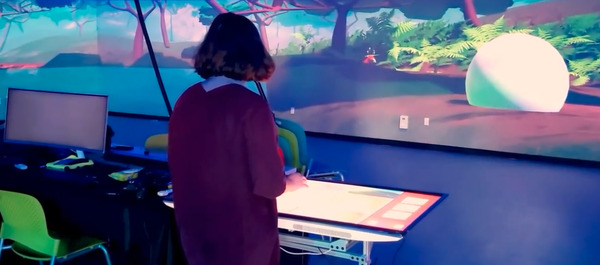

My goal for Create(x) is for it to be a space where students can develop emerging technology systems and software that augment spaces in ways that change how we interact with computers both for research and entertainment purposes. The core goal is to teach students skills in immersive design, communication, and programming so that they may create innovations that enhance their practice, whether they are a storyteller, scientist, or artist. We welcome and engage in interdisciplinary research with partners to understand how tech developed at the lab can be used to support projects and practices outside the walls of our lab.

What kinds of skills are required for your role? How did you acquire them?

The major skills I have are in design and programming. I developed skills in visual design from my time as an undergraduate at the Academy of Creative Media at UH Mānoa. Growing up, I always loved to draw, but through my time as an undergraduate I gained a foundation in useful skills such as digital art techniques, 3D modeling, and different techniques in animation that to this day is a large part of the work that I do. I learned programming from my education in Computer Science at UH Mānoa, where I have done my Bachelors, Masters, and now PhD in. Without all of these skills, I could not develop the projects that I do. I wanted to become a video game developer when I started university, which is why I tried learning skills from all parts of the process because I did not know exactly what I wanted to do. In the end being a jack-of-all trades has helped me immensely.

The other important skill is organization. I think I got that skill from watching my mom who is a very organized person and runs her own business. Without having good organization and efficient processes it would be very hard to implement the projects we work on, even if we somehow had the world’s best artists and programmers on the project.

What was the journey to becoming an interactive media designer? Why did you choose such a unique career? How did you know that this is what you wanted to do?

I was actually going to go to university enrolled in Travel Industry Management. I was put in the AOHT (Academy of Hospitality of Tourism) track in high school. It wasn’t my first choice, but I did enjoy my teachers and classmates on the track. My experience with that, and from advice from counselors, I was convinced that if I wanted a good job and to stay in Hawaiʻi I should aim to be something like a hotel manager. However, I was also taking Japanese when I was a senior, and we had a project where we could design any form of media for our project as long as everything was in Japanese. This became an excuse to try to learn how to develop a video game. I made a little RPG on Construct2. That is when I wanted to become a game developer, and I think in like a month or two before I started university I managed to change my major to both ACM and Computer Science.

While I was in university I took Dr. Jason Leigh’s video game design class. It was at this time LAVA was first being developed because Dr. Leigh was newly hired. As time went on, I hung around LAVA and eventually got hired there as an undergraduate research assistant. It was through my experience at LAVA that made me see there are more pathways than just becoming a video game developer. So now I am here where I am today.

We are very glad you didn’t study TIM! What do you enjoy most about your career? What are some of your greatest challenges?

What I enjoy most is designing things. The general process of brainstorming, planning, and creating is one of my greatest joys in life. It could be as simple as designing my desk space to designing the complex projects we implement at the lab. The joy of my career is that I am able to design things that can enrich and support our lāhui. For instance, working at the Office of Indigenous Knowledge and Innovation means that the projects I work on include community co-design and impact. We have intentions of developing and utilizing emerging technology to aid in the development of processes and actions to improve environmental stewardship and heal land in ways that align with ancestral practice and values.

I believe the greatest challenge is time and capacity. I wish I had more time in the day to work on projects, and had more capacity to work on the myriad of pono projects that are in various stages of development in Hawaiʻi. That is why I am focused on holding space for teaching and not just research. I believe if there were more people from Hawaiʻi who had similar skills that I have learned and a passion for cultivating abundance for both land and people, we could develop great things. In Hawaiʻi there is no shortage of people who aloha ‘āina. However, there is only a small community of us that also have skills in immersive and interactive design and the capacity to hold those types of careers since the cost of living continues to rise here. I try to take my own action as well as support initiatives that will make these skills more accessible to students and develop an industry for this sort of work.

Where do you get your inspirations?

The typical places: my family, friends, teachers, and Hawaiʻi itself. When times are hard I have always turned to spending time in a good story whether through a book, video game, or movie; talking story with beloved people; or spending time in familiar places such as my favorite beaches or places in the mountains. Doing these things is refreshing and brings me the inspiration to continue working and brings new ideas and perspective to my work.

Of your many successes, which project or accomplishment are you most proud of?

It’s hard to say I’m proud of any of my accomplishments. As an artist, I do fall in the common feeling of “things could have been done better.” Often my feelings are more like I’m thankful that it happened. The work I do is complex in that it can’t be built by a single person. I may be the one who can take credit for developing a piece of software, but held within most of our projects are data, knowledge, and stories collected by others such as community experts, scientists, or cultural practitioners. Without the willingness to share that knowledge, these projects wouldn’t exist. So I’m thankful for the opportunity to work with others and I suppose I am proud that they trust me. I aim to continue to develop and perpetuate practices to earn and honor that trust.

Can you share a bit of a current project?

A current project that I am working on is called the Makawalu Editor (for now, it’s a working title). I can’t talk too much about the details as it is still in development, but it essentially is an interface to visualize environmental data using a tangible interface. It grew from a project that was developed at LAVA in collaboration with HECO called the ProjectTable 2.0. A prototype of this system was recently used as a part of an internship run by the Office Indigenous Knowledge and Innovation and Malama Puʻuloa. The interns learned the basics of ArcGIS and story maps to tell their own stories connected to the land they helped care for during the time of their internship. The Editor was used to help visualize their maps.

Your projects have included designing apps and “serious games.” What are some of these? What does success of these projects look like to you?

For me, the success of any project is if it develops some sort of knowledge or capacity in the player. For instance, for Kilo Hōkū VR, where we developed a VR application to teach the basics of modern Hawaiian wayfinding practices, the success for me was providing an alternative to studying in cases where students may not have access to clear skies or a planetarium.

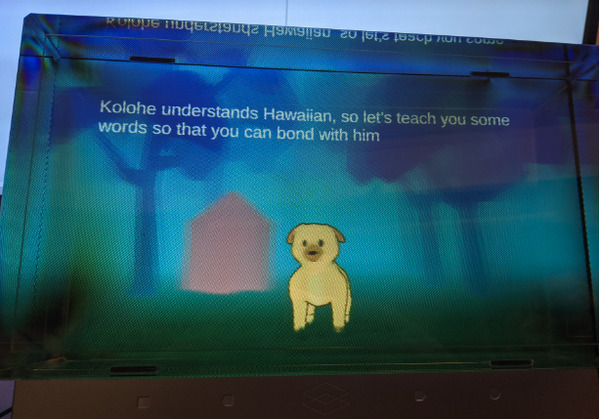

Wao Kiʻi, a project I developed for my master’s thesis, aimed to be a tool to learn basic Hawaiian environmental vocabulary without using English. This is done through a character’s features and attributes that change based on where tiles with Hawaiian words or phrases are placed. So for example, if you place an ʻiʻiwi tile onto the board, the character will turn into an ʻiʻiwi. If you place a lele tile onto the board, the character will start to fly. This creates the connection between the word and its meaning. A further connection is made as in Wao Kiʻi, the scene you are in determines the vocabulary that is presented to the user. So for instance, if the scene is meant to resemble Wainiha Valley on Kaua’i, the vocabulary will be related to a specific place rather than general Hawaiian words. In this way, this development of understanding of the relationship between words, meaning, and place is what I consider a success.

The ultimate measure of success is accessibility. This is a metric I’m still trying to work on improving. Lots of what I work on is inaccessible due to the tech it’s created on, but slowly things are changing.

How do you avoid letting the pressures of innovation and creativity overwhelm you?

Trying to be innovative and creative to me is a joy, and I think I have had enough failures in my life that I’m not afraid of it. I also don’t feel the pressure that any project has to be my magnum opus, because there is no way of knowing what that will be until it happens. Sometimes what I think would be a stellar idea is actually my worst one in practice. I enjoy the ride, and if it doesn’t work out, that only means I know how to do better next time.

What are your hopes and dreams for the year and beyond in terms of your career and what you would like to send out into the world in the future?

For this next year(-ish) my hopes and dreams revolve around finishing my dissertation. There is a lot I put on pause to finally get that last fancy paper. Once I get that degree my hope is to continue to be working in a place where I can be in a position to continue designing technologies and systems that support community abundance, knowledge, and healing. I also want to be able to pass on the skills that I’ve learned so that in the future there will be many local students who can do what I do and do it better. Together they can take advantage of whatever emerging technology develops in the future and use it to also create abundance and capacity in a pono way.

Do you have any experiences as a woman of color in your field that you might share with our readers? What would you like to see change in the industry regarding the acceptance of BIPOC creators?

In my industry there should be more women & BIPOC. That’s still where we are at. In Hawaiʻi I think we have a lot more POC compared to other places, but in my perception there is still a lack of women and Indigenous computer scientists considering the population of Hawaiʻi and the DEI initiatives that exist. In my experience, I do try to make an extra effort to help women, Indigenous, & LGBTQ+ students where I can (recommending them to positions, advising on funding possibilities, getting them access to lab space). But often what limits these students are two things:

- life circumstances that commonly affect a person based on their background

- the inevitable stress and turmoil from being a minority.

I’ve had younger students who, for instance, don’t have as strong financial support from parents due to multiple reasons, which means that the student has to take on extra work to be able to make a living wage, which limits the time they can dedicate to their studies and ability to do extra curricular work that would help them develop as professional. So they get left behind or have to drop out totally.

Personally in my experience I have dealt with things such as:

- giving a presentation about a project that involved Hawaiian cultural ideas and practice, and the first response from the audience was someone making an inappropriate joke about Hawaiians.

- people when I bring up projects like Wao Ki’i that teach ‘ōlelo Hawai’i, their response is “Is Hawaiian a real language? Like can you have full conversations in it?”

- being asked multiple times by the same person “You developed this?”

- classmates not letting you do any of the work on class projects because “it’s ok, they can just do it” and so on.

I think that these sorts of challenges and headaches are not unique to Computer Science but many other fields. All I can say is that the most important thing is to find your community. Having friends and colleagues that share your hopes, values, and struggles is the best way to be able to weather any circumstance and situation that may come your way. When the weather gets rough, you can keep each other afloat.

What beliefs is your work challenging?

I think that by working in the spaces that I do, I’m proving that tech is not out of reach for any group or community. When I give demos to people, they often ask where I went to high school. They then take a guess like, “Punahou? Kamehameha?” I then laugh because I went to public school on an outer island for my entire life. They have an assumption that I must be a private school grad to do the level and kind of work I do.

I also think that my work also challenges the notion that Indigenous knowledge and technology do not mix. In my opinion, Kānaka Maoli have always been tech enthusiasts. From taking advantage of the printing press to installing electrical infrastructure; I think our kupuna were good at seeing new technology, quickly making it their own, and using it to their advantage. This is not to say we need to adopt every new technology; we still have to gauge what is pono. But generally I get the feeling that, especially people not from Hawaiʻi, think Kānaka Maoli are anti-tech and anti-science. They couldn’t be more wrong, and I think (and truly hope) projects we develop help them see that. And if not, we will keep building great things regardless.

What advice would you give a student interested in joining your field?

Generally: Find what interests you and stick with it, even when things feel difficult. Learning skills in both art and programming is like riding a bike through an area with a lot of hills. At first it’s hard while you try to learn foundational skills. It will feel like cycling up a hill. But then your understanding will click into place and you will feel like you’re coasting down. Then you begin to learn a new more advanced topic, and yet again there is another hill to climb. Learn how to enjoy the ride and challenge. Make sure you find some buddies that will ride with you. Learn when to get off your bike and walk to go easy on yourself. Push your buddies up the hill when they need it, and let them help you when you need it.

Specifically: Go download a game engine like Unity3D, Unreal, or Godot. Go download Blender. Think of an easy game idea, like pong, pinball, space invaders, etc. Look up tutorials and try to build your idea. You will start to understand what it takes to make a game when you attempt to make one. See which parts that you like, what parts that you can’t stand, and what parts you feel excited to improve on. From there you will discover if you will like this field, and what part of the process you may want to focus on. This will determine if maybe you are more of an engineer, artist, or production manager sort of person. Go find others that are doing this. I can’t emphasize this enough, having community is important.

What’s your online presence like? Are you on social media?

I’m a computer scientist who is awful at social media. But I do lurk there. Because I’m not very active I don’t get many messages. I’m trying to change this. For those who know me, they know how often I say, “Oh I probably should have taken a picture/video of this.”

And niele questions, if youʻd like to answer:

Who is your biggest supporter?

My partner and my family. I try to be on top of my game when I am at work and in public. So when I get home I am often acting goofy and tired. I am thankful for their patience.

What’s your favorite memory of growing up on Kauaʻi?

Rain. It feels like it rarely rains on O’ahu (at least where I live). I miss waking up the sound of the wind blowing the rain against my window. I often miss the smell. I also am fond of the memories of my brother, friends, and I just wandering around as kids. We would go walk through fields and collect bugs and things. We would feed flowers to someone’s cows. We’d steal eggs from chickens. We would dig a giant hole in the sand for no reason other than to marvel that we dug a big hole.

What’s your favorite app? Which app do you wish you could’ve had a hand in creating?

I wouldn’t want to create any of the apps I enjoy, because if I had a hand in creating it I’d be much more critical of it and may not enjoy it. I really like an app called Notion. It helps both in work and just keeping track of things that I like.

This was so cool, Kēhau! Mahalo nui loa for sharing your manaʻo with us!

To learn more about Kēhau Noe and her work at the Create(X) lab at the University of Hawaiʻi at West Oʻahu, visit her website at KehauNoe.com.

Images courtesy of Kēhau Noe.