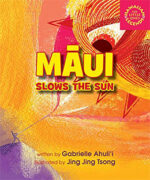

Like most Native Hawaiians, author Gabrielle Ahuliʻi grew up hearing the beloved legends passed down from generation to generation.

Like most Native Hawaiians, author Gabrielle Ahuliʻi grew up hearing the beloved legends passed down from generation to generation.

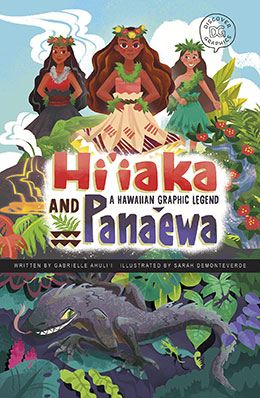

Best known for her popular series, Hawaiian Legends for Little Ones, and now for her first graphic novel, Hi’iaka and Panaewa, Gabrielle beautifully retells these classic stories for today’s young readers and their grown-ups.

Why is it so important for children to know the myths and legends of their ancestors? Gabrielle explains in an interview at Brightly:

Exposure to stories and legends of cultural significance in early childhood can give children a deep sense of respect for the place they live and an opportunity to engage with the culture around them. Access to and engagement with Native Hawaiian stories empowers children of Native Hawaiian descent by arming them with knowledge to help navigate their world as Indigenous people…If a child understands the world around them from a cultural perspective, they are not only able to engage more deeply with their culture, but to create more meaningful connection across cultures as well.

We totally agree.

Aloha e Gabrielle. For those who haven’t met you, could you please tell us a little about yourself?

My name is Gabrielle Ahuliʻi Ferreira Holt, and I was born and raised on Oʻahu. I live in the ahupuaʻa of Makiki, which is also the ahupuaʻa of the school I work at. I am the school librarian at Hanahauʻoli School, a 105 year old progressive elementary school.

Where did you grow up? What high school did you grad from?

I grew up in Honolulu, and I was fortunate to attend both Hanahauʻoli School and Punahou School. Hanahauʻoli gave me the gift of critical thinking, a love of learning, and creative problem solving, while Punahou school widened my horizons and gave me the gift of learning ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi for four years.

Go Buff n’ Blue! Who is your biggest supporter?

I live an incredibly privileged life in that I have no lack of supporters. I have countless people in my life who step up, both physically and mentally, and are constantly and consistently on my team. I want to recognize my family, my partner, my mentor, my editor at Beachhouse, my friends and colleagues at Hanahauʻoli, and the lāhui for always giving me everything I need.

Why did you become a writer? What inspired you to write for children?

I didn’t ever see myself as a writer; as a kid, I was an incredibly lazy writer. I didn’t  connect to writing in the way that I deeply connected to reading. I became friends with someone who publishes books for children in Hawaiʻi while I was in the Library Sciences program at UH. At the time, I was focused on Hawaiian / Pacific Librarianship, and when she heard about my passion, she approached me with a writing project. She and I worked so well together that we published six adaptations of moʻolelo together. She allowed me to see myself as a writer.

connect to writing in the way that I deeply connected to reading. I became friends with someone who publishes books for children in Hawaiʻi while I was in the Library Sciences program at UH. At the time, I was focused on Hawaiian / Pacific Librarianship, and when she heard about my passion, she approached me with a writing project. She and I worked so well together that we published six adaptations of moʻolelo together. She allowed me to see myself as a writer.

What do you enjoy most about writing for kids? What are some of your greatest challenges in writing for children?

Since I am a school librarian, I get to workshop ideas and rough drafts with my students. Their feedback is invaluable. I hear their voices in my head when I am crafting a story. I love that I get to essentially collaborate with my students. Some of them are such powerful, descriptive writers that truly inspire me.

After their Hawaiʻi Island trip, one child wrote about the “braided lava.” Another child wrote the phrase “Pele runs her hand along creation,” and I was just blown away. Just being around their sincere, creative energy makes me a better person and a better writer.

My biggest challenge is keeping stories simple. Too often, people feel that children need bells and whistles in a story to keep them engaged. Nothing is further from the truth! The most enduring, meaningful narratives for children are often the most simple but profound. If you have something to say, say it truthfully, meaningfully, and in the language of the world you have built.

Congratulations on your new graphic novel, Hiʻiaka and Panaewa! Can you share a bit about the book? Without giving too much away, what is it about?

Congratulations on your new graphic novel, Hiʻiaka and Panaewa! Can you share a bit about the book? Without giving too much away, what is it about?

This book is a re-telling of Hiʻiaka and her first major encounter with one of the moʻo of Hawaiʻi – Panaʻewa. My re-telling simplifies her journey a lot. Itʻs for younger readers and for those who may not have a lot of context for who Hiʻiaka is, so she sets of on this adventure with a slightly different goal than what is discussed in the original ʻoli.

What inspired you to choose that topic for your first graphic novel?

When I was approached to write this, I suggested three Hawaiian moʻolelo (hoping that this one was the one the publishers would connect to). I wanted to write a moʻolelo with a female protagonist, and I wanted to bring more of Hiʻiakaʻs story to younger readers.

What was your favorite part of writing your graphic novel? What was most challenging?

I love reading and doing research, so I really like that part of the process. I want to make sure that my adaptations are faithful, while also being able to give them my own voice and perspective. I wasnʻt used to creating books in a graphic novel format, so the biggest challenge was thinking about what I wanted each panel to look like – not that I necessarily told the illustrator exactly what to draw, but I needed to think about what my words needed to say and where the images could help support the rest of the story.

What was the journey to getting that book published like?

Capstone approached me to write an entry in their ongoing Discover Graphics series in December of 2021 and I spent 2022 working on the manuscript. It was published in December of 2022. They found me because of my first series of Hawaiian Legend adaptations, which has indeed opened many doors for me.

What characteristics do you love best about the protagonist(s)?

I love Hiʻiaka as a character because although she is powerful, she is also fallible and realistic. I love how courageous she is, but also how cocky she can be. I didnʻt get to include this in my re-telling, but there is a point in her story when she is participating in a surf contest, and she says, “Aia a ʻane e uhi ke kai i ke kua o ke kuahiwi o kea, a laila, kū koʻu nalu – When the sea rises and covers Mauna Kea, then that is my wave.” So brave, and so bold! I just love her so much and want more of her epic available for children to enjoy.

You are also the author of a successful series of board books. What inspired you to write about folk tales for your first books?

You are also the author of a successful series of board books. What inspired you to write about folk tales for your first books?

I think there is a true need for moʻolelo to be accessible for young readers – we have a few very, very good adaptations, but I want children to have as many anthologies and books about Hawaiian gods and goddesses as there are about the Greek ones. I want more Native Hawaiian voices represented as the tellers of these moʻolelo, and I want a wide variety of moʻolelo told.

What are your hopes and dreams for the year and beyond in terms of your writing career and what you would like to see published in the future?

I would love to continue to perpetuate the culture of literacy that Kanaka have built. It is a privilege to get to be someone who can write these moʻolelo down for posterity, so I hope and dream that I continue to do it and do it in a way where I make my community and lāhui proud to read them.

My next goal or wish is to create an anthology of Hawaiian moʻolelo for middle grades — 3rd to 6th. There is a real need there. The anthologies that do exist are good resources for adults. I want older elementary age children to be excited about the Hawaiian pantheon of Gods and Goddesses in the same way many are obsessed with Greek or Norse mythology.

My next goal or wish is to create an anthology of Hawaiian moʻolelo for middle grades — 3rd to 6th. There is a real need there. The anthologies that do exist are good resources for adults. I want older elementary age children to be excited about the Hawaiian pantheon of Gods and Goddesses in the same way many are obsessed with Greek or Norse mythology.

There are not a lot of stories for kids by Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander or BIPOC writers. Why do you think that is? What do you think we can do the change that?

I do feel we are seeing a paradigm shift in publishing culture. Many are being more critical of the books that take up space in the canon of childrenʻs literature and giving it a second glance. I feel that it is more diverse than when I was developing my reading skills, certainly.

However, it really does boil down to: You canʻt be what you canʻt see. The only books that I read as a child with a Hawaiian character in it were either so wildly misrepresented as to verge on offensive, or written by a non-Hawaiian person. I think that in order to fix this, we have to empower ourselves to take charge, shed our imposter syndromes and say, “I can do this, I can tell this story.” In that way, we can invest in a future where children have seen themselves represented in their literature and are encouraged to not only seek out more, but add on to what has been created.

However, it really does boil down to: You canʻt be what you canʻt see. The only books that I read as a child with a Hawaiian character in it were either so wildly misrepresented as to verge on offensive, or written by a non-Hawaiian person. I think that in order to fix this, we have to empower ourselves to take charge, shed our imposter syndromes and say, “I can do this, I can tell this story.” In that way, we can invest in a future where children have seen themselves represented in their literature and are encouraged to not only seek out more, but add on to what has been created.

Which of your books did you have the most fun writing? Which were the most challenging?

All were such interesting challenges that it’s hard to rank them. I loved doing the research piece for all the board books — even though the adaptations are quite short, I wanted to do the tradition of moʻolelo service and tried to find and read as many versions as I could. I loved writing all of them!

What beliefs are your books challenging?

I want to challenge the belief that Hawaiʻi is just this static place that visitors simply “experience”. I want people to understand that every piece of Hawaiʻi is a moʻolelo in itself; that every person (visitor, settler or ʻōiwi) here has a responsibility to take care of Hawaiʻi and acknowledge those moʻolelo.

I want to challenge the belief that Hawaiʻi is just this static place that visitors simply “experience”. I want people to understand that every piece of Hawaiʻi is a moʻolelo in itself; that every person (visitor, settler or ʻōiwi) here has a responsibility to take care of Hawaiʻi and acknowledge those moʻolelo.

Can you share a bit about your next book?

I’ve just finished an ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi translations of my first six board books with Beachhouse. David Del Rocco helped me immensely with the translation process (I needed some language support — some of my grammar was a little rusty!) I am beyond excited for those re-publications to come out. I would love to read them aloud ma ka ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi someday soon to a group of children!

What advice would you give an aspiring writer?

Write what you know and in your own voice, writing is not a solo process, the project is never truly finished, treat your characters with empathy and as if they are sitting in the room with you.

Write what you know and in your own voice, writing is not a solo process, the project is never truly finished, treat your characters with empathy and as if they are sitting in the room with you.

What kinds of books do you enjoy reading? Any favorites?

I love reading and my superpower is that I am an extremely fast reader, so I am able to read a lot in a short amount of time. I love authors like Ali Smith who play with the conventions of what a novel is and have such a specific voice. I love all genres – although I donʻt necessarily gravitate towards romance or thrillers (except a book called Razorblade Tears that I thought was stupendous).

Hereʻs a list of authors and/or books that I love:

- Ali Smith (Seasonal Quartet, The Accidental, How to be Both)

- Rachel Cusk (Outline trilogy)

- Hernan Diaz (Trust)

- Elif Batuman (The Idiot)

- Otessa Moshfegh (My Year of Rest & Relaxation, Lapvona)

- Bernadine Evaristo (Girl, Woman, Other)

- Emma Cline (The Girls, Daddy, The Guest)

- Jesmyn Ward (Salvage the Bones, Sing, Unburied, Sing)

- Madeline Miller (Song of Achilles, Circe)

- Robert Jones Jr. (The Prophets)

- Miriam Toews (A Complicated Kindness, Women Talking)

- Tommy Orange (There, There)

- Yoko Ogawa (The Memory Police)

More authors: Mohsin Hamed, Helen Oyemi, Andrea Levy, Bryan Washington, Michael Ondaatje, Lisa taddeo, Juhea Kim, Chanelle Benz, Lauren Groff, Zadie Smith, Luis Alberto Urrea, Brandon Hobson)

I have so many!

Can you share a bit of your current work?

I just went to Hawaiʻi Island with some students and was isnpired by Waiānuenue / Rainbow Falls and the moʻolelo of Kuna the moʻo. I started drafting a story to tell my students the second night we were there, so this is a work in progress:

The moʻo took silent steps toward her. The moʻo was covered in a sickly translucent set of scales, as if the rays of the sun could not reach him. His eyes were a deep mottled grey. Hina thought of the lava fields south of Hilo, the smooth lava that in some light looked like bodies strewn across a plain. His eyes gave her that same unsettled but awe-struck feeling.

The moʻoʻs tongue slicked out to wet one of those grey eyes. “Hina of Hilo — you meet my eyes as if we are equals. But you do have manners, so I will not strike you down here. I have long tired of you and your kind coming to this island, assuming that you can shape the earth around you with no consequence.”

Hina opened her mouth to argue but remained silent. Sometimes silence was better.

The moʻo continued. “Your son, the famous Māui, has a hook. He will bring me this hook that he has used to reshape the heavens itself, or you will die here, in this pool. This pool is cold and the current is strong, and the sea of this coast is violent and unforgiving.”

Hina thought. Why should Māui bring this monster his hook?

The moʻo smiled slyly. “Why should your son bring me this hook, you may be thinking. Simply: he does not deserve this extraordinary tool. This hook belongs to the old Gods, those that were born from the deep roiling depths and grew alongside the ferns and fish and birds.”

“The gods themselves gave that hook to my son, and he has only used it to serve others. As I have taught him.” Hina stood up straighter.

“Who does he serve when he cracks the sea floor to pull islands to the surface? Who does he serve when he bends even the sun to his selfish will?” The moʻo spoke calmly, but Hina could sense the fury pulsing through the monsterʻs veins. His tail tapped slowly on the wet cave floor.

“He serves his family and his people. As is correct,” Hina responded simply. “The responsibility of gods and their family is to help and protect the humans who live with us.”

The kids must’ve loved this! Do you have a website? Are you on social media? Do your readers contact you? What do they say?

My website is gabrielleahulii.com. I donʻt really have social media in a professional “writer” capacity. Most people contact me through my website. I get messages about how they discovered my books or I get images of children reading them. I love that a lot. I also get to meet people when I do readings, which is always so fantastic!

It was wonderful meeting you, Gabrielle. Mahalo nui for sharing your manaʻo, and best wishes always for your continued success!

To read more about Gabrielle, including her work on literacy in Hawaiʻi, visit her website, GabriellaAhulii.com. Photo courtesy of author.

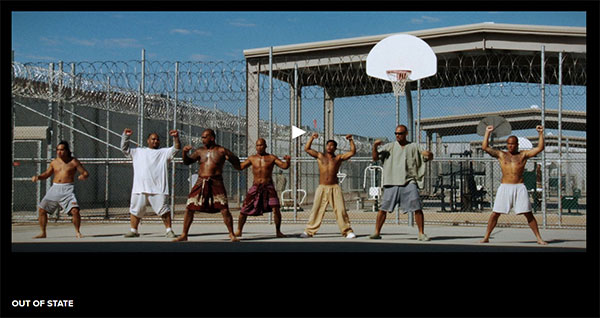

Ciara Leinaʻala Lacy is a talented writer-producer-director whose passion is telling stories influenced by her Native Hawaiian heritage.

Ciara Leinaʻala Lacy is a talented writer-producer-director whose passion is telling stories influenced by her Native Hawaiian heritage.