Native Hawaiian author Megan Kamalei Kakimoto is a rare literary gem: a storyteller of YA (young adult) and adult subject matter that is authentically rooted in Native Hawaiian life experiences.

storyteller of YA (young adult) and adult subject matter that is authentically rooted in Native Hawaiian life experiences.

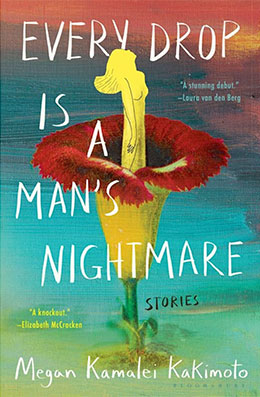

Her USA Today National Bestseller, Every Drop is a Man’s Nightmare, is a short story collection that reviewers describe as “powerful coming-of-age stories that prove it is possible to be many things, all the time, all at once” (Author Amy Hempel), “rich and wise, humming with confidence” (New York Times Book Review), and “a blazing, bodily, raucous journey through contemporary Hawaiian identity and womanhood” (Bloomsbury Publishing)

We are so pleased to talk story with Megan today.

Aloha kaua e Megan. Congratulations on your new book! For those who haven’t met you, please tell us a little about yourself?

Mahalo nui! My name is Megan Kamalei Kakimoto, and I’m a Japanese and Native Hawaiian writer living in Honolulu. I recently received my MFA at the Michener Center for Writers, where I studied both fiction and screenwriting. Aside from my lifelong passion for writing and reading, I’m also a runner, a stationary cycling enthusiast, and a proud pet mom to a kolohe dog and queen-of-the-house cat.

Where did you grow up? What high school did you grad from?

I grew up in Makiki and graduated from Kamehameha Schools Kapālama

Me, too! Go Warriors! Can you share a bit of your upcoming short story collection, Every Drop is a Manʻs Nightmare? Without giving too much away, what is it about?

Every Drop is a Manʻs Nightmare is a collection of 11 stories centering native Hawaiian and hapa identity, female sexuality, local superstitions, and the lasting wounds of colonization. Many of the stories lean into the speculative, and at their heart are uniquely Hawaiian experiences that play out in a contemporary landscape.

What inspired you to write these stories? Is there any particular story that speaks to you?

I’ve always loved writing short stories and living in their world of brevity and subtlety. These stories in particular came to me over a long period of time (the first story I began around 2015, I believe) and emerged out of a love and admiration of our Hawaiian community and particularly the mana and ferocity of our women.

In terms of stories that speak to me, I’d say “The Love and Decline of the Corpse Flower” has a special place in my heart, in that it came to me almost fully formed. I felt an instant affinity for the women in this piece, and knew right away I wanted to do right by them.

I love that story, too. What was your favorite part of writing your collection? What was most challenging?

My favorite part of writing this collection is also my favorite part of writing stories in general—I love living in the language and taking the time to play with my sentences. Usually on the line level is where characters first emerge for me, so seeing how these women slowly started to reveal themselves in the collection’s many stories was such a pleasure.

The biggest challenge I faced was more of an internal struggle in that for many months I feared how these stories would be received by kānaka readers. I so badly want to make native Hawaiian readers proud, which creates a twofold emotional response for me, in that I also have lots of anxiety around disappointing them. While I know there’s no universal or monolithic Hawaiian experience, I couldn’t help but feel paralyzed by the fear that the experiences I was writing into through these stories simply weren’t valid, and this brought a lot of pressures to stories that were still in their infancy. I really had to work through this fear for a while, and sometimes it still creeps up.

Oh, yes, I understand the pressure. What characteristics do you love best about the protagonists in Every Drop? Are they modeled after specific people?

I just love messy women and seeing them be messy on the page! I also really admire when characters in fiction are afforded the full range of their humanity, which I tried to do for the women in Every Drop. While none of the women are modeled after specific people, there are so many strong, resilient, messy women among my friends, family, and community who I’m sure have seeped into these characters with or without my knowledge.

What was the journey to getting Every Drop published like? How long did it take to write your book?

It’s strange — the journey feels both incredibly long and very compressed simultaneously! There’s a pretty wide range in terms of when these stories came to be; I began a few of them as early as 2015, while one I wrote as recently as 2021. I had been nursing the majority of the book’s stories for many years before I was able to conceive of them as a collection. Then COVID hit, I began my MFA at the Michener Center for Writers remotely and really got to work on curating a collection and taking it very seriously. I signed with my agent Iwalani Kim in April 2021, after which we spent over six months revising and polishing the stories before she went out on submission. The book sold at auction fairly quickly after that.

Why did you become author? Have you always wanted to be an author?

Yes, it’s the only thing I’ve ever wanted to be and honestly likely one of the only things I’m good at! In all seriousness, I’ve taken artmaking seriously since I was a child and always knew I wanted to do something in the literary space. For a while, I dreamed of becoming a journalist, then a novelist. Reading widely and being exposed to so many incredibly gifted authors was what propelled forward my passion to become an author myself.

What do you enjoy most about writing? What are some of your greatest challenges?

I love the playful and generative space of starting a story. Before any pressure is put on it to become the thing it wants to be, there exists a sense of endless possibility that just thrills me. I think one of my greatest challenges is learning when to end something. I have a tendency to overwrite (which is why I also take so much time with the revision stage), and it can be hard for me to see an ending clearly because I often just want to keep going with a character, a world, an atmosphere, etc.

What are your hopes and dreams for the year and beyond in terms of your publishing career and what you would like to see published in the future? Can you share a bit about what you’re working on next?

I would love to see the story collection welcomed into the larger literary landscape, particularly because there are so few works being published on a large scale by native Hawaiian authors. There are plenty of books written about Hawaiʻi and Hawaiians, but few have been penned by Hawaiian authors, and it’s really important for me to champion Indigenous writers and their work.

In terms of future projects, I’m on contract with Bloomsbury (my publisher) for my first novel. It’s tentatively titled Bloodsick, and while I won’t give too much away, I can share the book is invested in the topics of motherhood, menstruation, and anxiety.

What beliefs are your work challenging?

One of the beliefs I hope my work challenges is the aforementioned idea of a monolithic Hawaiian experience that stems from a lack of representation of Hawaiian experiences in contemporary literature. I also hope to push against the idea that Indigenous characters in fiction should be represented well and admirably—this expectation ends up stripping them of so much of their humanity. Instead, I wanted these stories to champion characters who made bad decisions and said the wrong things—and were ultimately still capable of receiving and returning love.

What advice would you give an aspiring writer?

Take pleasure in the work. It’s easy for writers to aspire to publicity and rave reviews and awards, but no external recognition can compare to the pleasures of a fully realized story. A writing career also takes a lot of grit, persistence, and patience, so it’s important for you to locate your love and inspiration first and foremost in the work itself.

What’s your online presence like? Do your readers contact you? What do they say?

I have a humble online presence, mostly in the form of my website and Instagram. A few readers have contacted me with overwhelmingly kind things to say about the collection, which truly means the world to me. When the readers in question are kānaka, my heart absolutely soars.

And now a few niele questions, if you’d like to answer. Who is your biggest supporter?

My parents are my biggest, longest running supporters, without question. My partner Van has also been in my corner since day one.

Is there a fun fact youʻd like to share about yourself with readers?

Since book promotion began, I’ve become obsessed with taking stationary rhythmic cycling classes as a stress relief and now cannot imagine my life without it!

What kinds of stories do you enjoy reading? Any favorites?

I love stories that yield deep insights into what it means to be human and in a body. I also gravitate toward stories that subvert my expectations, are playful on the line level, and demand an attention to the language, sometimes so much so that I must return to them again and again. Just a few story collections that stand out to me: The Visiting Privilege (and especially “Honored Guest”) by Joy Williams, Sabrina & Corina by Kali Fajardo-Anstine, Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz, Sing to It by Amy Hempel, and most recently The Sorrows of Others by Ada Zhang.

This has been so fun! Mahalo nui, Megan, for talking story and sharing your mana’o with us. Our best wishes always for your continued success! To learn more about Megan and to read more of her work, visit her website and follow her on Instagram.

Images courtesy of Megan Kamalei Kakimoto

First there are three, for a reason. Three is my favorite number. Lots of things come in threes — three wishes, the triple crown, three parts of an atom, three-part story structure, three musketeers, junkenpo — but most important to me are my three daughters.

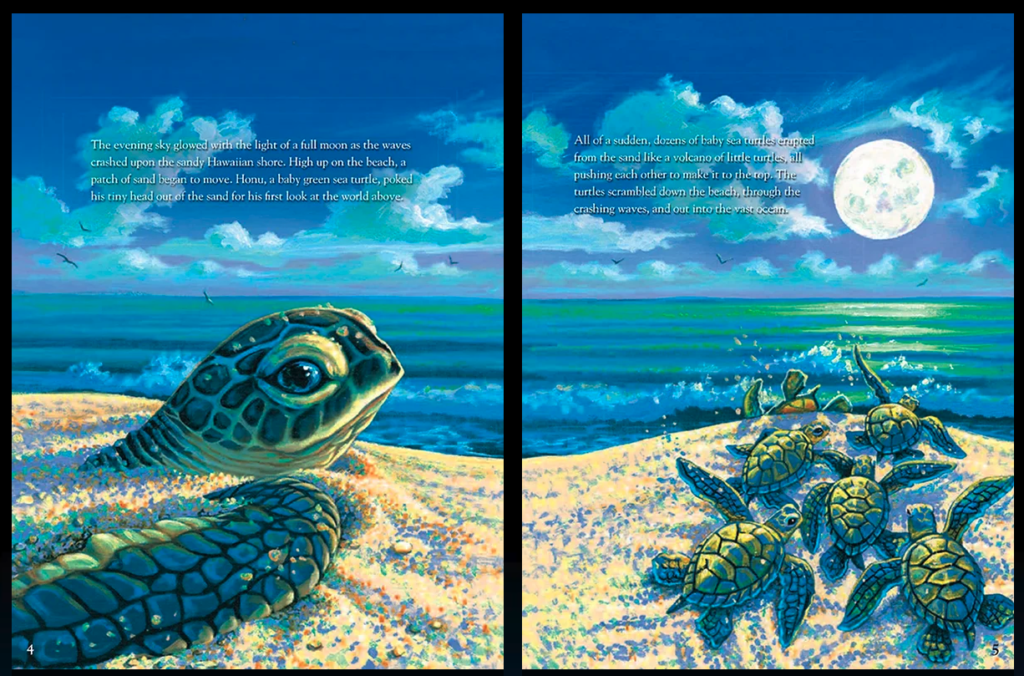

First there are three, for a reason. Three is my favorite number. Lots of things come in threes — three wishes, the triple crown, three parts of an atom, three-part story structure, three musketeers, junkenpo — but most important to me are my three daughters. Kōlea tend to return to the same Hawaiʻi neighborhoods each year, and Iʻm always happy when I see them on our Central Oʻahu street. I can tell theyʻre around when I hear their distinctive keek-KEEK!

Kōlea tend to return to the same Hawaiʻi neighborhoods each year, and Iʻm always happy when I see them on our Central Oʻahu street. I can tell theyʻre around when I hear their distinctive keek-KEEK!