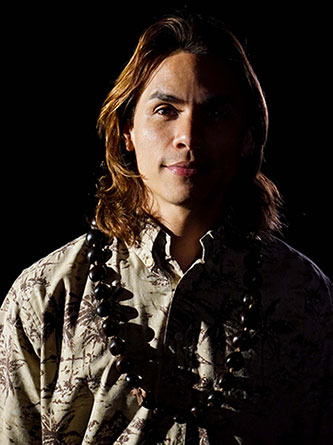

Native Hawaiian filmmaker Keoni Kealoha Alvarez is a man of many talents and interests. He is a director, producer, teacher, and author, and most of all, a storyteller.

Native Hawaiian filmmaker Keoni Kealoha Alvarez is a man of many talents and interests. He is a director, producer, teacher, and author, and most of all, a storyteller.

We are pleased to welcome Keoni to our blog today as the first post of 2024.

What inspired you to go into the arts and filmmaking, especially producing?

I was always into creating art — acrylics, charcoal and sculpting art pieces — following in the footsteps of my father and brothers. I won a few awards for my accomplishments early on and made a few art pieces for art shows locally. My art has always had a Hawaiian theme — Hawaiian landscapes, people or native plants.

My first production experience was back in my senior year in high school [Pahoa] I produced and directed “Romeo and Juliet.” Thanks to supportive teachers and classmates who believed in me, I focused on drugs and suicide awareness and prevention. I rewrote the script to the English we speak today because it was important for everyone to understand its strong message. I got all my classmates to be characters in the play or help backstage. I asked all the stores and restaurants in Pahoa town to donate food or monetary donations to make this play possible. It was the biggest performing art production ever at Pahoa High School.

What do you like best about being a producer?

I love being a producer because no one changes your story. When you have that platform as the producer, you are in charge from beginning to end of what the film will look like. I happened to be the producer, director, editor and main character of my film, Kapu: Sacred Hawaiian Burials. These were all hard and difficult roles to fill. I felt it was important for me to be in control of these roles because the subject was so kapu (forbidden) in Hawaiian culture. I realized how much was at stake if I had someone else in control of this story and misled people or changed our history and the impacts it could have on our people. So this was a huge responsibility to tell this story well.

I wanted to share my story through Hawaiian eyes — my eyes and my words. Looking back it was the best choice I made in my life. Even though it took 23 years to create and complete, it was well worth every step to completion. I can honestly say I have no regrets. The feedback I received from our Hawaiian people make me proud of the film.

What are some of your greatest challenges you face as a filmmaker?

My great challenge, especially here in Hawaiʻi, has been to believe in myself, that it is ok to express myself and that there are people who will stand by me. One of my first jobs was a film editor for a director, Jay Curlee, former director of sports for our local news statoin KHON2 News. His small production business was involved in many different productions: live performances, commercials and documentaries. Jay was the best boss and taught me everything about filming and editing. I worked for him for over ten years. Jay allowed me to gain skills and experience by working on other major film productions and my personal film projects.

Can you share what it was like to work on your film, Kapu: Sacred Hawaiian Burials? What made you decide on that subject?

I loved working on this 23 year project. It was not easy. Lots of tears, money, time and hard work went into this project. This was my story and my life, and I wanted to do the best that I could. For over 30 years my family has been protecting an ancient Hawaiian burial cave which has been in our family and kept secret for many years. I found out a land developer had purchased the land which contained the burial cave. He wanted to bulldoze the burial cave to build over it. I was heartbroken and sad that outsiders would ever try to do such a thing. So I picked up my camera and started to film my story. I filmed many interviews across the neighbor islands of Hawaiian elders sharing their stories of traditional Hawaiian burial practices.

My film was finally completed in 2022, and our burial cave was saved. Today I own the burial cave and act as the steward for this historical site. Kapu: Sacred Hawaiian Burials is shining light on this important topic protecting and preserving ancestral burials of indigenous culture.

Click the images to view the film on PBS Hawaiʻi.

You were with ʻŌlelo Community Media for four years. What did you like best about your work there?

The number one thing I loved about working at ʻŌlelo was allowing people to share their 1st amendment right to freedom of speech uncensored. I loved working with the staff and all the independent producers I’d met over the years. Teaching my students the basics of filmmaking and seeing them grow have been the most rewarding. Some of my students have surpassed me and created award winning films. I am so proud of everyone I had the opportunity to meet and teach. There is no place like ʻŌlelo Community Media.

What do you think are the most important elements of filmmaking?

I believe in allowing people the time to speak their true and honest feelings and viewpoints. This is the core of any great story or interview. I always look for people who have a sense of style, how they carry themselves and speak. Their voices are just as powerful as any celebrity or big box office movie when they are given the chance to share their story. When you find [a great story], you know you’ve struck gold.

Have you had to handle a difficult conflict or unexpected challenges in your career as a producer?

A the producer wears many hats. There is never a time that everything is easy. Every interview and every scene has some sort of difficulty. Audio, lighting and camera are a few things that will go wrong on film shoots. I always plan for the worst. This way I never get surprised or experience major setbacks.

If you had to choose a favorite project, which would it be and why?

I’ve traveled the world several times working on Norwegian Cruise Line. I was hired on the broadcast team onboard. It was amazing. I met so many people and visited so many places in the world. I would love to travel again incorporating Hawaii as the main subject to teach people about our Hawaiian heritage, history and our cultural places.

Can you share a bit of your current work?

My current work is to create a nonprofit organization which protects and preserves Hawaiian burial from desecration. This non-profit will have a team dedicated to help Hawaiian families identify ancestral burials and provide lawyers, legal assistance, land environmental impact studies, and land acquisition to protect historical burials from desecration. We will use expert teams in archeology field to monitor all known historic burials in Hawaii.

Where do you get your inspirations?

My inspiration comes deep within me of the experiences of things I learned and experiences which have failed. That always helps me on my next move to staying relevant as a Hawaiian filmmaker. I take that personal data then decide if the idea will cause more good than harm. I learned a lot from filmmaking; my decision making process means it is easier to see a clear path to reach my next goal.

What are your hopes and dreams for the year and beyond in terms of your artistic career and what you would like to see for your career in the future?

I would love to own my own multi-media center for the community, a performing art theater in my hometown, and my own personal art gallery.

What beliefs is your work challenging?

The most challenging thing, which is ironic to me, is that outsiders do not understand the meaning of sacred. That word is so simple, but they make it seem difficult to understand because they cannot have it or be a part of it. That’s the sad part living in Hawai’i. To us Hawaiian people, our ancestral ʻiwi (bones) are sacred. Some non-Native Hawaiians who move to Hawaiʻi want to take part of those bones, and to me thatʻs sick and disturbing.

What tips would you give aspiring filmmakers just starting their careers?

I would say always plan that the road will be rough with lots of obstacles and no shortcuts. Stay focused, finish what you start, and NEVER give up. At the end of the day, you will look back and say it was worth every step. You are strong, you are brave and you can still be humble.

What is your proudest accomplishment?

Iʻm proud of creating a website hawaiianburials.com dedicated to bringing awareness about the traditional practices and beliefs of Hawaiian burials. It’s been receiving very well its 2nd place on the topic on google.

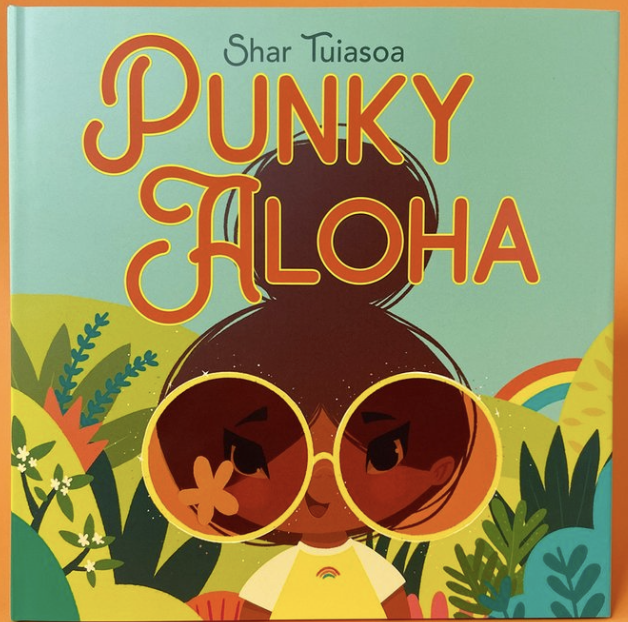

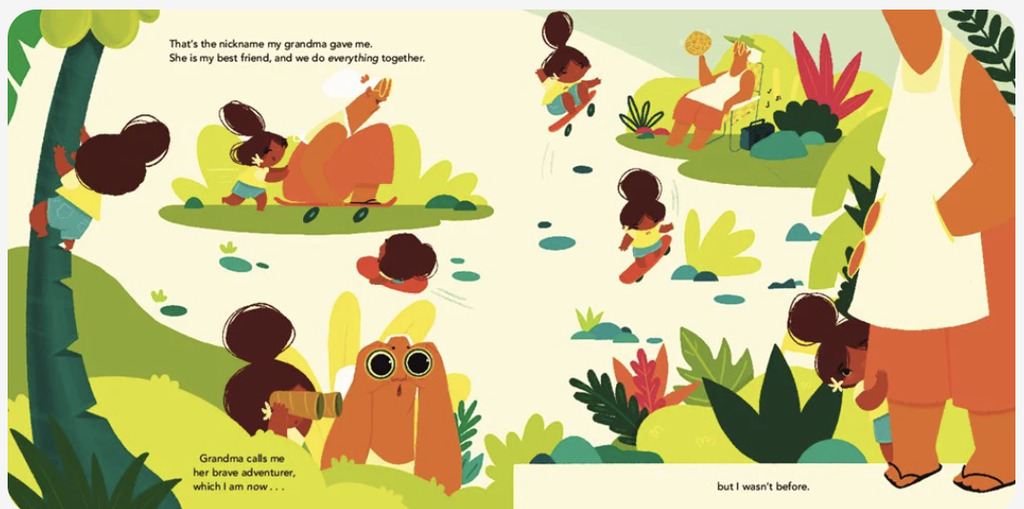

I also wrote four books about Hawaiian burials. Keoniʻs independently published books include: Kapu: Sacred Hawaiian Burials, Kapu: The Hole Truth, Kapu: Hawaiian Burial Methods, and a childrenʻs picture book, The Boy and his Hawaiian Cave. All are available on Amazon.

About your books, tell us what you enjoy most about writing, especially for kids? Can you share a bit about your book, THE BOY AND HIS HAWAIIAN CAVE? Without giving too much away, what is it about?

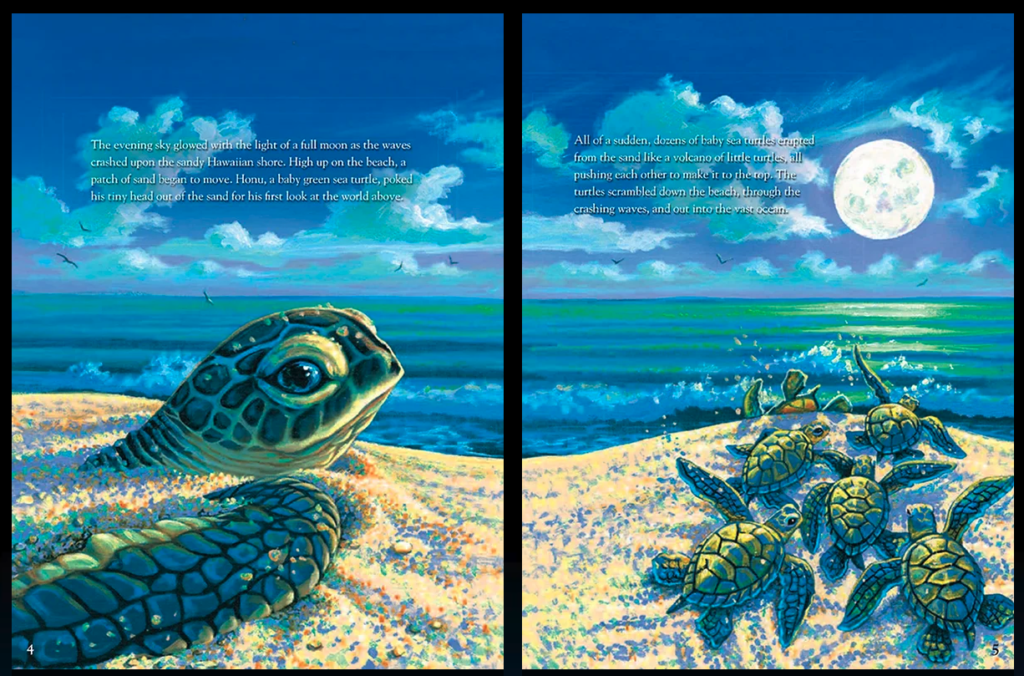

The Boy and his Hawaiian Cave is one of my proudest achievements because it made it possible to share the Hawaiian value of aloha and respect about ancestral burials to young children. This book is about a Hawaiian boy named Keoni who is on a journey gathering special gifts of aloha for his family burial cave. The colorful illustrations and exciting story help children to appreciate Hawaiian culture. My readers describe the book as a personal memoir. This book took two years to complete, and I am very happy with the outcome.

You choose to independently publish your books. What was that journey like? Would you do it again?

Self-publishing was the best thing I did. It gave me the opportunity to be creative while having no boundaries to share this important story. I was able to work with my personal team of writers who gave me valuable feedback. Additionally, I am not obligated to any publishing contract. I own 100% of my copyright. My print-on-demand book print is high quality but at the lowest author print cost. This means readers can afford to purchase prints of my books.

Can you share a bit about the projects you’re working on next?

Community Multi Media Center, Hawaii Island Theater — Performing art theater and Keoni Alvarez Art Gallery

How can readers contact you? What’s your online presence?

My website is hawaiianburials.com. (Keoni also has a YouTube channel, Hawaiian in the City. His social media includes Facebook, and Instagram.)

A few of niele questions ke ʻoluʻolu. What is your favorite film of all time, and what makes it a favorite?

I love Martin Scorsese’s film Goodfellas. I love everything about its story line, plot, drama and narration. Scorsese uses so many different styles of storytelling, and it all works. He chooses the right time and place to add his signature to his films. That’s what makes him great. He is an artist of film.

Who is your biggest supporter?

My mom is my biggest supporter and my biggest producer lol. She was there for me from the beginning. Mahalo, mama. I love you!

Yay! What do you enjoy doing in your down time?

Playing with my dog, cleaning my yard, going to the beach, surfing, painting something, and going to the gym — anything quiet is always a good thing for me.

This was fun talking story with you, Keoni! We look forward to hearing more from you in the future!

Images courtesy of Keoni Kealoha Alvarez, stills from PBS Hawaiʻi.

First there are three, for a reason. Three is my favorite number. Lots of things come in threes — three wishes, the triple crown, three parts of an atom, three-part story structure, three musketeers, junkenpo — but most important to me are my three daughters.

First there are three, for a reason. Three is my favorite number. Lots of things come in threes — three wishes, the triple crown, three parts of an atom, three-part story structure, three musketeers, junkenpo — but most important to me are my three daughters. Kōlea tend to return to the same Hawaiʻi neighborhoods each year, and Iʻm always happy when I see them on our Central Oʻahu street. I can tell theyʻre around when I hear their distinctive keek-KEEK!

Kōlea tend to return to the same Hawaiʻi neighborhoods each year, and Iʻm always happy when I see them on our Central Oʻahu street. I can tell theyʻre around when I hear their distinctive keek-KEEK!